|

|

Angkor’ literally means ‘Capital City’ or ‘Holy City’.

‘Khmer’

refers to the dominant ethnic group in modern and ancient Cambodia.

In its modern usage, ‘Angkor’ has come to refer to the capital city

of the Khmer Empire that existed in the area of Cambodia between the

9th and 12th centuries CE, as well as to the empire itself. The

temple ruins in the area of Siem Reap are the remnants of the

Angkorian capitals, and represent the pinnacle of the ancient Khmer

architecture, art and civilization. Angkor’ literally means ‘Capital City’ or ‘Holy City’.

‘Khmer’

refers to the dominant ethnic group in modern and ancient Cambodia.

In its modern usage, ‘Angkor’ has come to refer to the capital city

of the Khmer Empire that existed in the area of Cambodia between the

9th and 12th centuries CE, as well as to the empire itself. The

temple ruins in the area of Siem Reap are the remnants of the

Angkorian capitals, and represent the pinnacle of the ancient Khmer

architecture, art and civilization.

At its height, the Age of Angkor was a time when the capital area

contained more than a million people, when Khmer kings constructed

vast waterworks and grand temples, and when Angkor’s military,

economic and cultural dominance held sway over the area of modern

Cambodia, and much of Thailand, Vietnam and Laos.

|

The First Century: Indianisation

Southeast Asia has been inhabited since the Neolithic era, but the

seeds of Angkorian civilization were sown in the 1st century CE. At

the turn of the millennium, Southeast Asia was becoming a hub in a

vast

commercial trading network that stretched from the Mediterranean to

China. Indian and Chinese traders began arriving in the region in

greater numbers,

exposing the indigenous people to their cultures, though it was

Indian culture that took hold, perhaps through the efforts of

Brahman priests. Indian culture, religion (Hinduism and Buddhism),

law, political theory, science and writing spread through the region

over a period of several centuries, gradually being adopted by

existing states and giving rise to new Indianised princedoms.

Funan and Chendla: Funan and Chendla:

Pre-Angkor

Though the newly Indianised princely states sometimes encompassed

large areas, they were often no larger than a single fortified city.

They warred among themselves, coalescing over time into a shifting

set of larger states. According to 3rd century Chinese chronicles,

one of China’s principal trading partners and a dominant power in

the region was the Indianised state of Funan centered in today’s

southern Vietnam and Cambodia. There is evidence that the Funanese

spoke Mon-Khmer, strongly indicating a connection to later Angkorian

and Cambodian civilization.

Funan was predominate over its smaller neighboring states, including

the state of Chendla in northern Cambodia. Over the later half of

the 6th century, Funan began to decline, losing its western

territories. Chendla, already in the ascendant, conquered the Khmer

sections of western Funan, while the Mon people won the extreme

western section of Funan in present day Thailand. Later, Chendla

seems to have gone on to conquer the remainder of Funan, signaling

the beginning of the ‘pre-Angkorian’ period. Chendla flourished but

for a short time. The third and last king of a unified Chendla,

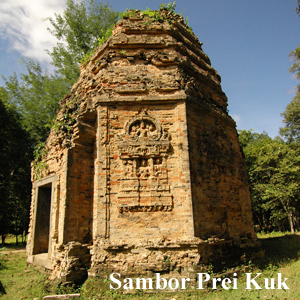

Isanavarman I, constructed the pre-Angkorian temples of Sambor Prei

Kuk near modern Kampong Thom city. (If you come to Siem Reap from

Phnom Penh by road, you will pass through Kampong Thom. With a few

spare hours, it is possible to make a side trip to these

pre-Angkorian ruins).

Under Isanavarman I’s successor, Chendla disintegrated into smaller

warring states. It was briefly reunited under Jayavarman I in the

mid-7th century, only to fall apart again after his death. On

traditional accounts, Chendla finally broke into two rival states or

alliances, ‘Land Chendla’ in northern Cambodia/southern Laos, and

‘Water Chendla’ centered further south in Kampong Thom.

802CE: The Beginning 802CE: The Beginning

Jayavarman II was the first king of the Angkorian era, though his

origins are recorded in history that borders on legend. He is

reputed to have been a Khmer prince, returned to Cambodia around

790CE after a lengthy, perhaps forced stay in the royal court in

Java. Regardless of his origin, he was a warrior who, upon returning

to Cambodia, subdued enough of the competing Khmer states to declare

a sovereign and unified ‘Kambuja’ under a single ruler. He made this

declaration in 802CE in a ceremony on Kulen Mountain (Phnom Kulen)

north of Siem Reap, where he held a ‘god-king’ rite that legitimized

his ‘universal kingship’ through the establishment of a royal

linga-worshiping cult. The linga-cult would remain central to

Angkorian kingship, religion, art and architecture for centuries.

Roluos: Roluos:

The ‘First’ Capital

After 802CE, Jayavarman II continued to pacify rebellious areas and

enlarge his kingdom. Before 802CE, he had briefly based himself at a

pre-Angkorian settlement near the modern town of Roluos (13km

southeast of Siem Reap). For some reason, perhaps due to military

considerations, he moved from the Roluos area to the Kulen

Mountains. Some- time after establishing his kingship in 802CE, he

moved the capital back to the Roluos area, which he named

Hariharalaya in honor of the combined god of Shiva and Vishnu. He

reigned from Hariharalaya until his death in 850CE.

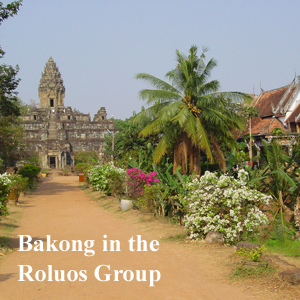

Thirty years after Jayavarman II’s death, King Indravarman III

constructed the temple of Preah Ko, the first major member of the

‘Roluos Group’, in honor of Jayavarman II. He then constructed

Bakong, which was the first grand project to follow the

temple-mountain architectural formula. When visiting these temples,

note the deep, rich, detailed artistic style in the carvings that

were characteristic of the period.

Indravarman III also built the first large baray (water reservoir),

thereby establishing two more defining marks of the Angkorian

kingship - in addition to the linga-cult, the construction of temple

monuments and grand water projects became part of kingly tradition.

The Capital Moves to Angkor The Capital Moves to Angkor

Indravarman III’s son, Yasovarman I, carried on the tradition of his

father, building the East Baray as well as the last major temple of

the Roluos Group (Lolei), and the first major temple in the Angkor

area (Phnom Bakheng). Upon completing Phnom Bakheng in 893CE, he

moved his capital to the newly named Yasodharapura in the Angkor

area. The move may have been sparked by Yasovarman I’s violent

confrontation with his brother for the throne, which left the Royal

Palace at Roluos in ashes. With one exception, the capital would

reside in the Angkor area for the next 500 years.

Koh Ker: Koh Ker:

A Brief Interruption

The exception took place in 928CE when, for reasons that remain

unclear, there was a disruption in the royal succession. King

Jayavarman IV moved the capital 100km from Angkor north to Koh Ker,

where it remained for 20 years. When the capital returned to Angkor,

it centered not at Phnom Bakheng as it had before, but further east

at the new state-temple of Pre Rup (961CE).

Apogee: Apogee:

The Khmer Empire at Angkor

An era of territorial, political and commercial expansion followed

the return to Angkor. Royal courts flourished and constructed

several major monuments including Ta Keo, Banteay Srey, Baphuon, and

West Baray. Kings of the period exercised their military muscle,

including King Rajendravarman who led successful campaigns against

the eastern enemy of Champa in the mid 10th century. Just after the

turn of the millennium, there was a 9-year period of political

upheaval that ended when King Suryavarman I seized firm control in

1010CE. In the following decades, he led the Khmer to many important

military victories including conquering the Mon Empire to the west

(capturing much of the area of modern Thailand), thereby bringing

the entire western portion of old Funan under Khmer control. A

century later, King Suryavarman II led several successful campaigns

against the Khmer’s traditional eastern enemy, Champa, in central

and southern Vietnam.

Under Suryavarman II in the early 12th century, the empire was at

its political/territorial apex. Appropriate to the greatness of the

times, Suryavarman II produced Angkor’s most spectacular

architectural creation, Angkor Wat, as well as other monuments such

as Thommanon, Banteay Samre and Beng Melea. Angkor Wat was

constructed as Suryavarman II’s state-temple and perhaps as his

funerary temple. Extensive battle scenes from his campaigns against

Champa are recorded in the superb bas-reliefs on the south wall of

Angkor Wat.

By the late 12th century, rebellious states in the provinces,

unsuccessful campaigns against the Vietnamese Tonkin, and internal

conflicts all began to weaken the empire. In 1165, during a

turbulent period when Khmer and Cham princes plotted and fought both

together and against one another, a usurper named

Tribhuvanadityavarman seized power at Angkor.

In 1177 the usurper was killed in one of the worst defeats suffered

by the Khmers at the hands of the Cham. Champa, apparently in

collusion with some Khmer factions, launched a sneak naval attack on

Angkor. A Cham fleet sailed up the Tonle Sap River onto the great

Tonle Sap Lake just south of the capital city. Naval and land

battles ensued in which the city was assaulted, burned and occupied

by the Cham. The south wall of Bayon displays bas-reliefs of a naval

battle, but it is unclear whether it is a depiction of the battle of

1177 or some later battle.

Jayavarman VII: The Monument Builder Jayavarman VII: The Monument Builder

The Cham controlled Angkor for four years until the legendary

Jayavarman VII mounted a series of counter attacks over a period of

years. He drove the Cham from Cambodia in 1181. After the Cham

defeat, Jayavarman VII was declared king. He broke with almost 400

years of tradition and made Mahayana Buddhism the state religion,

and immediately began Angkor’s most prolific period of monument

building.

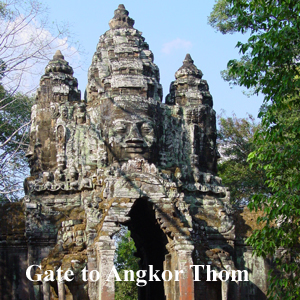

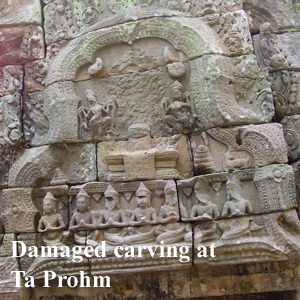

Jayavarman VII’s building campaign was unprecedented and took place

at a frenetic pace. Hundreds of monuments were constructed in less

than a 40-year period. Jayavarman VII’s works included Bayon with

its famous giant faces, his capital city of Angkor Thom, the temples

of Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei and Preah Khan, and hundreds of others.

The monuments of this period, though myriad and grand, are often

architecturally confused and artistically inferior to earlier

periods, seemingly due in part to the haste with which they were

rendered.

After a couple of days at the temples, you should begin to recognize

the distinctive Bayon-style of Jayavarman VII’s monuments. Note the

giant stone faces, the cruder carving techniques, simpler lintel

carvings with little or no flourish, the Buddhist themes to the

carvings and the accompanying vandalism of the Buddhas that occurred

in a later period.

At the same time as his building campaign, Jayavarman VII also led

an aggressive military struggle against Champa. In 1190 he captured

the Cham king and brought him to Angkor. In 1203 he annexed all of

Champa, thereby expanding the Khmer Empire to the eastern shores of

southern Vietnam. Through other military adventures he extended the

borders of the empire in all directions.

Jayavarman VII’s prodigious building campaign also represents the

finale of the Khmer empire as no further grand monuments were

constructed after his death in 1220. Construction on some monuments,

notably Bayon, stopped short of completion, probably coinciding with

Jayavarman VII’s death. His successor, Indravarman II continued

construction on some Jayavarman VII monuments with limited success.

The End of an Era The End of an Era

Though the monument building had come to a halt, the capital

remained active for years. Chinese emissary Zhou Daguan (Chou Ta-Kuan)

visited Angkor in the late 13th century and describes a vibrant city

in his classic, ‘Customs of Cambodia’.

Hinduism made a comeback under Jayavarman VIII in the late 13th

century during which most of Angkor’s Buddhist monuments were

systematically defaced. Look for the chipped out Buddha images on

almost all of Jayavarman VII’s Buddhist monuments. Literally

thousands of Buddha images have been removed in what must have been

a huge investment of destructive effort. Interestingly, some Buddha

images were crudely altered into Hindu lingas and Bodhisattvas.

There are some good examples of altered images at Ta Prohm and Preah

Khan.

Jayavarman VIII also constructed the final Brahmanic monument at

Angkor - the small tower East Prasat Top in Angkor Thom. After

Jayavarman VIII’s death, Buddhism returned to Cambodia but in a

different form. Instead of Mahayana Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism

took hold and remains the dominant religion in Cambodia to this day.

After the 13th century, Angkor suffered repeated invasions by the

Thai from the west, pressuring the Khmer and contributing to the

capital being moved from Angkor. After a seven-month siege on Angkor

in 1431, King Ponhea Yat moved the capital from Angkor to Phnom Penh

in 1432. This move may also have marked a shift from an

agrarian-based economy to a trade based economy, in which a river

junction location like Phnom Penh rather than the inland area of

Angkor would be more advantageous. After the move to Phnom Penh, the

capital of Cambodia moved a couple of more times, first to Lovek and

then Oudong, before finally settling permanently into Phnom Penh in

1866.

After the capital moved from Angkor, the temples remained active,

though their function changed over the years. Angkor Wat was visited

several times by western explorers and missionaries between the 16th

and 19th century, but it is Henri Mouhot who is popularly credited

with the ‘discovery’ of Angkor Wat in 1860. His book, ‘Travels in

Siam, Cambodia, Laos and Annam’ is credited with bringing Angkor

its first tourist boom. .

|